Review

by Michelle Liu,| Synopsis: |  |

||

In a realm beneath the seas dwell the elementals that maintain the balance of the natural world. Chun, a young plant elemental, is enthralled by the wonders of the human world. Despite her elders' warnings to stay away from mankind, she strays too close and gets caught in a fishing net. Although she escapes unharmed, the boy who saves her loses his life. Overcome with guilt, Chun trades away half of her lifespan to give the boy another chance at life, vowing to protect his soul until he can return to the earth. But breaking the cycle of life and death comes at a far steeper price than she alone can pay. As the laws of nature turn upside-down, her decision threatens to rock the very foundation of her world. |

|||

| Review: | |||

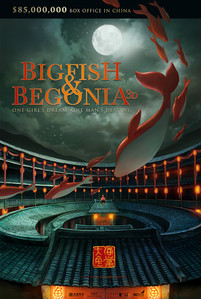

According to director Liang Xuan, the image of a fish rising to the sky first came to him in a dream. That's a good place to start when processing the film that image became: fantastic and breathtakingly gorgeous, Big Fish and Begonia is a film straight out of the recesses of a dream world. It's a few parts classic poetry, a few parts Ghibli fantasy-adventure, and a few parts something else entirely, all woven into the fabric of Chinese folklore in a way rarely seen in major animated films. Combining the mythical with the personal, Big Fish tells a story both age-old and refreshingly intimate while breaking new ground for Chinese animation. In gestation for over twelve years, Big Fish and Begonia is first and foremost a visual feast. Every set immaculately designed, every background a painting, the film is a masterpiece in the hands of co-director Zhang Chun, who graduated from Tsinghua University's Academy of Arts and Design. Assisting in animation production was Studio Mir, better known in the West for The Legend of Korra and Voltron: Legendary Defender. With the combined forces of Mir and B&T, the result is a lavish production virtually unprecedented in Chinese feature animation. A few moments of awkward CG integration aside, there's not a moment in the entire film that doesn't feel like a dream given form. (Folks expecting nifty combat animation might be better off looking elsewhere, however; Big Fish is a distinctly non-fighting film. Chinese yes, wuxia no.) But as lovely as the film looks, its real draw is its storytelling. Pulling together elements from Taoist literature, Big Fish is brimming with ideas about loyalty, sacrifice, and mortality, thrusting heavy emotions on its young characters from early on. Liang's script doesn't shy away from complicated subjects. Not only does Chun have to understand death at 16, she also has to assume the blame for it. In a crucial moment, she is forced to confront the possibility that for every life she saves, another one might be lost. Conflicts between personal debt and social responsibility abound; the “right” choice, if there even is one, is often difficult. Ultimately, it's love – romantic, filial, or otherwise – that offers the characters a bit of hope, though even that comes with its own strings attached. Although it doesn't always have answers to the questions it raises, Big Fish is remarkably thoughtful for a film of its stripe. In particular, the conflict between filial loyalty and personal morals seems especially relevant in the context of modern Chinese youth. Liang was in his early 20s when he wrote the script, having freshly dropped out of university in pursuit of a career less orthodox than engineering. In light of that, Big Fish and Begonia seems to reflect the clash between what Chinese youths are expected to be (supportive of the family above all else, in accordance with Confucian principle, making stable employment and marital status paramount) versus what they want to be (beholden to their own moral compass, willing to take risks as an artist). Even selfless acts for other people might be viewed as selfish by the family or community. It's definitely a familiar dilemma to a Chinese (or Chinese-American, in my case) audience. It's also worth noting that the script feels carefully put together. Every element introduced turns up again later; virtually no thread goes unresolved. Even minor plot detours, like a brief episode in the lair of a rat woman, have thematic purpose. In contrast to the dreamlike gallery of souls, the rats in the sewer are a reminder of the ugliness and rot of death, existing in tandem with the Taoist notion of the soul's ascension. The wry comedy that sneaks its way into this segment is a nice bonus. For a first feature film, Big Fish is impressively tight. Frankly, if I had to voice a complaint with the film, it's that there's simply too much going on. So much happens over its 100-minute runtime that it's almost difficult to process one emotional turning point before the next. Still, given the choice between a rote hero/villain dynamic and a bleeding-heart love letter to the culture of my youth, I'd take the latter, no matter how messy. Your mileage may vary, of course, but the novelty of the film's worldview might still warrant a look anyway. As for the English dub, it's a solid effort all-around. Stephanie Sheh captures Chun's quiet melancholy well, while Johnny Yong Bosch lends an effortless charm as her childhood friend Qiu. John White, meanwhile, delivers a delightful performance as Lingpo, the Keeper of Souls. The dub hews close to the Mandarin-language track in both script and tone, so if reading subtitles is in any way distracting to you, I'd recommend eschewing them to focus on the visuals. (Never mind how almost no one in the English cast can quite figure out how to pronounce Chinese names. The inevitable result of having localized so few Chinese films, I suppose.) All in all, Big Fish and Begonia is a special project, made with love and years of toil. Despite overreaching at times, the film tackles heavy subjects with delicacy, encouraging an audience of both young and old to think about life, death, and compassion. Add to that an aesthetic that owes as much to ink wash painters such as Qi Baishi as to a larger tradition of animation and you have a truly one-of-a-kind film. I can only hope that Liang Xuan and Zhang Chun continue to put out spectacular work in the future, whether in the planned sequel or another project entirely. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall (dub) : A

Overall (sub) : A

Story : A-

Animation : A-

Art : A+

Music : A

+ Unique and fully-realized fantasy setting, gorgeous art design, lovingly-crafted story about complex themes |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (7 posts) | | |||