Review

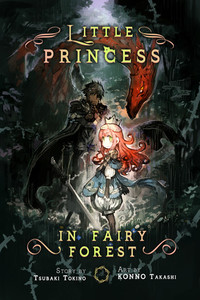

by Rebecca Silverman,Little Princess in Fairy Forest

Novel

| Synopsis: |  |

||

Kingdoms fall so quickly, and that of Princess Lala Lillia is no exception. When her scheming uncle kills her parents and usurps the throne, she's forced out of the palace at the tender age of six. Fortunately for her, the knight Gideon Thorn is able to hide her in the Black Forest, realm of the fairy folk. There they meet Spike Scale, a red dragon, and together the knight and the dragon agree to raise the princess until she's able to return to her kingdom. But the usurper isn't willing to wait for Lala to reappear, because he's in need of her royal blood to truly rule, and he will stop at nothing to get it. Can Lala's two foster fathers keep her safe and restore her to the throne? |

|||

| Review: | |||

Sometimes you just know that an author has done her research. That's true of Tsubaki Tokino's novel Little Princess in Fairy Forest: from names to folk songs to fairy tale elements, it's obvious that she really looked into the culture of European folktales to craft her story. While some notes are obvious – the hand of English folklorist Joseph Jacobs and Irish folklore scholar Thomas Keightly are very clear – others are more subtly integrated into the story, such as the works of The Brothers Grimm with a few nods that feel owed to Hans Christian Anderson and possibly Edmund Spenser. The result is a story with not only an interesting plot but a well-crafted world that is steeped in the author's research to the point where it makes the book feel almost like an old-fashioned children's story. That, of course, means that there's plenty of blood. Or at least implied bloodshed; Princess Lala doesn't actually see her parents die at the usurper's hand, but she's well aware that they are dead, and that helps to shape her worldview. Scenes told from the knight Gideon's point of view can get quite gruesome in an adventure story way, but the real disturbing content comes when, in his mania to get his hands on Lala, the villain orders all seven-year-old girls in the kingdom brought to him. Let's just say that the result is not pretty; the whole sequence of events is very upsetting. It is also crucial to the plot and to Gideon's character development, and in keeping with Tokino's research, it also is very much in line with many of the old folktales. The Bluebeard stories (AT312) all feature a man who kills multiple wives, which is essentially what's going on here, since, horribly, the usurper wants to marry Lala in order to legitimize his reign. By destroying all of the other little girls in the kingdom and leaving their bodies to be discovered, he is essentially reenacting elements of that tale type. Perhaps more interesting, however, is the character of Megan, the usurper's daughter, who contains elements of both the Snow White and Snow Queen stories. The novel contains elements of two different Snow White tale types – AT709, which is the story most people are familiar with, and 709A, where a baby girl is abandoned in the forest and is raised by two storks. Lala and Megan both fulfill roles from the stories, with Lala as the Snow White figure in both senses – but rather than two storks, she's raised by a dragon and a knight and she lives with Brownies rather than dwarves. (It's worth mentioning that in the Grimms' version of the tale, Snow White is mentioned to be seven years old, Lala's age.) Megan, on the other hand, is the Wicked Queen – by choice. Rumors say that before she was born, Megan's father sold her soul to the devil to eventually secure the throne for himself, and Megan is something of an ice princess as a result; she never shows emotion and is coldly calculating. Towards the beginning of the story she acquires a magic mirror which allows her to control the dead; although this isn't the exact usage of the mirror in Andersen's Snow Queen, the links between Megan's coldness and her similar dependence on a mirror makes comparisons feel apt. (A late scene involving mirror shards furthers this comparison.) But the truly fascinating way Tokino uses these stories is the fact that Megan made a conscious decision to become the Wicked Queen, something we can infer about the various characters who wear that mantle in the early tales but rarely, if ever, see happen. Megan, rather than having had her soul sold, may simply have been told so often that she didn't have one that she began to believe it, and instead of becoming a character like The Princess Who Never Laughed, she instead chose the role of the soulless with more agency: the villain. This puts her in direct opposition to Lala, who, although she absolutely shows that she can do things for herself, is still much more the protected princess than the active heroine. Since she's only seven years old and this story is for an audience rather older than that, it doesn't detract from the book, instead shifting the more active roles to her two substitute dads, Gideon and Spike. While Gideon certainly gets more narrative time, as well as some third-and-first-person narration, there's a lot of emphasis on the way he and Spike work together to care for and raise Lala during the year and a day (a typical folkloric measure of time) that they have her. While there isn't a huge amount of emphasis on the fact that this little girl is being raised by two fathers, that in itself feels like a good step towards normalizing nontraditional families, and virtually no one comments on the fact that two males, or even two different species, are co-parenting. It may not be the point of the novel, but watching Gideon and Spike protect their surrogate daughter becomes a charming piece of affirmation that family doesn't have to adhere to any specific norms. The writing in the novel is skillful, and Tokino seems very aware of how she uses folkloric themes and words, which adds to the overall world building and storytelling. Good choices have also been made in the translation, with the Spenserian “daemon” used instead of “demon” and Gideon's accent done without too much affectation, making it sound like a voice rather than a stereotype. The only real sour note may come from Tokino attempting to adhere to demographic norms (the novel has seinen origins) when Gideon describes the witch's voluptuous figure. It isn't offensively done, but it is jarring in comparison with the rest of the story. Little Princess in Fairy Forest is an interesting, well-researched piece of folkloric fiction. Drawing from European folk traditions and pairing them with the sensibility of late 19th century fantasy, the book is a good read overall. It's darker than many of Cross Infinite World's previous publications and definitely comes with a couple of trigger warnings for upsetting child-related content, but if you're a fan of dark fantasy or just think that a dragon and a knight sound like the coolest dads ever, this is worth your time. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : A-

Story : A-

Art : A

+ Research is apparent in the well-written story, art has a wonderful art nouveau sensibility that compliments the text, good choices in translation |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (6 posts) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about Release information about |

||