Review

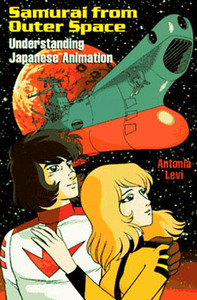

by Mikhail Koulikov,Samurai From Outer Space

Understanding Japanese Animation

| Review: | ||||||||

The concept of book-length studies of Japanese comics and animation is one that people most often have one of two opposite reactions to. Some consider them a waste of paper, an indulgence, and a rather misguided attempt to force seriousness and relevance on what is inherently not worth such attention. At the same time, plenty of others, either seeing the contemporary passion for analyzing everything, or believing that there is much more to anime than first appears, welcome such works wholeheartedly. And with books like Susan Napier's “Anime from Akira to Mononoke”, Anne Allison's “Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society” and Brian Ruh's forthcoming “Mamoru Oshii: The Stray Dog of Anime”, every indication is that both the public at large and the publishing world are open to this second view.

Depending on how you define your terms, anime has been around since 1917, the mid-1940's or 1957. Anime scholarship, however, is far younger. It wasn't until the late 1980's and early 1990's that the first articles that looked at anime from a critical, academic perspective appeared. And the first English-language book on anime did not appear until 1993. At first glance, Dr. Antonia Levi, who earned her Japanese history doctorate at Stanford and is currently affiliated with Portland State University, seems like the perfect person to write on anime and be credibly received, someone who can combine a respect for the medium and a familiarity with background material with a critical mindset. Being among the first people to approach anime with the intention of describing it, she also had her pick of both methods and goals. It is unfortunate indeed, then, that “Samurai From Outer Space” is, frankly, a mess. The book starts off well enough, with a thesis statement that, if not particularly unique, is both logical and very much in tune with the big question academics and the media grappled with throughout the 1990's. Levi proposes that because of a number of specific qualities, anime is the one form of popular culture members of America's “Generation X” will find most appealing and claim for their own. Unfortunately, several pages after the start of the book, she gets lost in the details. A long, meandering, and ultimately irrelevant discussion of the dubbing and subtitling release practices of the American studios simply wastes pages, while sweeping statements like “some Westerners…conclude that the Japanese prefer artificiality...Actually, what they prefer is symbolism" show that, rather than being able to evaluate aspects of Japanese culture objectively, Levi is one of those Westerners who become enamored with it and convinced that all things Japanese are mysterious, wonderful, and, by default, better than all things Western. She persistently compares Japanese and American animation, of course finding the latter lacking, but ignores both the influences Disney had on early anime and the fact that in terms of both storylines and target audiences, much of the anime she discusses has far more in common with American live-action TV series than with Saturday-morning cartoons. The major portion of Levi's book is taken up by several chapters analyzing different thematic aspects of anime: religion, heroes, women, death – all very general. At least potentially, this again allows the author to explore a number of avenues of approach to the subject, but what she actually winds up doing is regrettably limited. Perhaps playing to her strength as a scholar of Japan, most of what she does is show the ways in which certain specific things in Japanese cultural heritage, from the gods of Shintoist mythology to specific historical characters, are used or referenced in anime. Her methodology is erratic too, and is limited to simply picking titles, many of them on the obscure side (Detonator Organ, Roots Search, Venus Wars), saying a few words about each, and moving on to the next. There is little overall cohesiveness and certainly nothing in the way of establishing any kind of larger theory. Neither – unlike the later work of Napier – does she seem able to show that other cultural or media criticism, whether Western or Japanese, can apply to anime. Another frustrating thing – and inexcusable in a work that presents itself as an academic study – is the complete lack of footnotes or references. The reader is simply expected to take everything Levi says on faith. In addition, it wavers oddly between being a discussion of anime in and of itself and a description of anime industry and fandom in America. The book was published in 1996, and it is rather unsurprising that those sections that deal with the American side of the topic are badly dated, making them far more historical than in any way useful. In defense of Levi's book, many of the individual points she makes about both specific series and larger themes are interesting and valid. Being one of the first Westerners to write on anime at length, she did not have much to fall back on in terms of secondary sources or examples. And, her primary interest being history rather than media studies, it is easy to see that the approach she took plays to her strengths. Samurai From Outer Space is far from a perfect book, and it should certainly not be the only book anyone interested in the study of anime looks at. However, as an introduction to some of the ideas other scholars have explored since its publication, it serves its purpose. |

||||||||

| Grade: | |||

|

+ Accessible introduction to looking at anime from an academic perspective |

|||