Review

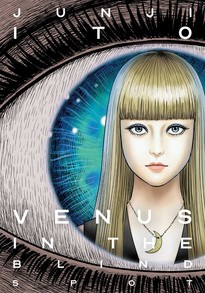

by Lynzee Loveridge,Venus In The Blind Spot

| Synopsis: |  |

||

Master horror manga creator Junji Ito is back with 10 new tales of dread and anxiety. This collection hones in on feelings of isolation, the desire to belong, and the what happens when someone's most intimate moments are invaded. Venus takes common fears and squarely centers women in society, their objectification, and doubt cast upon them to create an unsettling vision of reality that feels all too familiar. |

|||

| Review: | |||

Junji Ito is having a moment. While long considered a household name for horror manga in Japan, the last few years have seen a new push to bring him to the forefront of North American anime fandom. Viz has done an incredible job bringing his books stateside and featuring him in video content (he seems like a great sport) while Crunchyroll has offered fashion and merch related to his stories. Now, my penchant for horror is hardly unknown at this point and I've bought all of his releases currently available in print (and at least three t-shirts). I've enjoyed, at varying levels, all of his manga works and was likewise one of the most disappointed by that anime adaptation a few years back. Suffice to say, I'm a fan. Ito's manga regularly blends the comically absurd with unsettling horror but all of his stories have a through line of picking up on particularly common anxieties and blowing them up. At least I assume they're common; otherwise I'm just coincidentally easy mark for the topics Ito likes to focus on in his stories. Venus in the Blindspot runs the gamut of anxiety-inducing dread but many of the 10 tales within also focus on women and some of the unique struggles they face in society. This first becomes evident in "The Human Chair", a tried and true favorite by quintessential Japanese mystery author Edogawa Ranpo. The story has been adapted multiple times with variations on the theme; for example, Rampo Kitan: Game of Laplace opens with this story and exchanges the concept of a person inside a chair with chairs made of human body parts. This change in detail defeated what makes the original story so unsettling, and I'm glad to see Ito mostly stick with the original plot beats here even if his original, secondary twist at the end falls a bit flat. In "The Human Chair", a female author begins receiving letters from an anonymous writer that initially appears to be a story draft until the details start to closely mirror the author's actual life. Her new penpal claims to be a fan of her work and she slowly begins to realize he's much closer to her than she thinks. Ultimately, "The Human Chair" could be considered a variation of "the calls are coming from inside the house" as the author becomes convinced that somehow there's a man living inside her large, plush office chair. This is, of course, alarming to her as it would mean a hitherto unimaginable violation of her privacy. She pleads with her husband to get rid of the chair and insists there is a man inside. He ignores her requests as nothing more than her imagination as if she's in a fit of hysterics. Despite having a predictable ending, Ito's highly detailed and visceral style made the man-shaped indentation, complete with opened cans of food, disturbingly striking. Ito has a way of framing his page layouts so that just the right frames shock the reader the same way a horrifying revelation might in a movie. I've read the original Rampo story, which is told from the perspective of the man in the chair instead of the woman like in Ito's version. This offers a completely different mood than the original which, while startling, still attempted to get readers to understand the man in the chair. Like many of Rampo's stories, there is an overtly sexual element and Ito's version casts the unwilling participant as the main character. However, his unique "twist" at the end undid much of the satisfaction I got from the story. His second adaptation of Ranpo's oeuvre is less effective, focusing on the new wife in the Kadono clan, Kyoko. Through an arranged marriage, Kyoko is married to the slight and handsome Kadono. He by all appearances (and words) loves her dearly, yet for unknown reasons sneaks into a storeroom every night. His health appears to be waning and Kyoko, suspecting an affair, follows him on one of his outings where she learns that the object of his affections is an immaculate doll. Rampo had at least three stories centering on the concept of doll love, including "Unearthly Love" that is included in Ito's collection. The story itself feels less like horror and more like a strange tragedy (with some excellent face renditions here by Ito). "Perversion" was a regular subject of Rampo's stories and while "The Human Chair" centers on a feeling of violation, "Unearthly Love" focuses on a sense of betrayal as Kyoko learns that her husband's amourous confessions are only to satiate her while he has trysts with the female doll. She has in fact discovered that she is Kadono's "beard" and the similarities and framing of her discovering her husband with a doll versus a male lover were likely intentional on Rampo's part, as homoeroticism was another common theme in his stories although the author regarded it positively. Ultimately, the story is not so much frightening as it is tragic, especially when taking its ending into consideration. The titular story "Venus in the Blindspot" is one of the most effective as it grapples with an overbearing father and his desire to control his adult daughter and the terrible consequence of idolization. Mariko is a central figure in the UFO society where she and her like-minded male friends meet and discuss aliens while seeking out evidence of the truth. Her father founded the hobby group but it quickly becomes apparent that most of the members are more interested in potentially romancing Mariko than respecting her input on the topic. It's around this time that the members notice that they can no longer see Mariko: she starts to fade from view whenever she approaches them. This phenomenon causes mass hysteria in the group as the men become convinced they were subjected to an alien abduction and find scars hidden in their hair that suggests they were experimented on. Of course the conclusion is more terrarian than otherworldly and the story suggests Mariko's Venusian looks, whether visible or not, drive men to madness. Her experience has more than a casual similarity to idol culture and its most fervent fans. The club members grow violent in their self-proclaimed right to possess Mariko while her father's actions remove her agency from the story further. She is never given the opportunity to decide for herself what she wants romantically and meets a sorrowful end due to the club's own misogyny. Subsequent chapters are less effective, with the weakest being "How Love Came to Professor Kirida," a story about the obsessive love of women that transcend death to terrorize the men that rebuffed them. Similarly, "Keepsake" also features a man haunted beyond the grave after an eerie child is found born from the corpse of his dead wife. "Master Umezz and Me" is a humorous autobiographical chapter about Junji Ito and his childhood and later work intersecting with his favorite horror manga creator, Kazuo Umezz (Kazuo Umezu), the creator of The Drifting Classroom and Cat Eyed Boy. The opening chapter "Billions Alone" feels exceptionally relevant given the current times but would function exponentially better as a short series ala Uzumaki than as a single chapter. The final notable chapter is none other than "The Amigara Fault," a story that has perhaps been meme-ed to death at this point but still stands as a strong story about compulsion with an undercurrent of trypophobia. When an earthquake shifts the landscape, it reveals a series of human-shaped holes carved in the mountainside with no logical source. People from all around begin heading to the faultline after seeing its footage on television, each convinced they have found the hole made just for them. One after another, individuals begin filling their respective voids – seemingly compelled the moment they became aware of its existence. "The Amigara Fault" is a perfect example of "less is more," as no rhyme or reason is ascribed to the millenia-old holes or how they could be silhouettes of humans living in current time. Readers don't need that information to understand the inherent compulsion that begins affecting the people near the fault. It's a simple question, really. If you found some kind of hole or shape and knew you could fit in it, would you climb inside? Let's say it is only the size of your hand, would you reach in? Perhaps that desire to know and explore doesn't affect everyone, but it can nevertheless be simultaneously strong and terrifying . Venus in the Blindspot isn't a perfect collection. It presents a fear of women and the emotions associated with them just as much as it looks at how that fear can destroy lives. Still, there are enough spine-tingling tales within paired with Ito's continually outstanding art to warrant adding it to your horror library. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : B

Story : B

Art : A

+ Exceptional art all around with stand-out chapters focusing on Rampo's works and common anxieties |

|||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||